Pope Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors: Its Historical Roots, Content, and Evolving Influence

On December 8, 1864, Pope Pius IX issued the encyclical Quanta cura, accompanied by the striking Syllabus of Errors—a systematic index of 80 propositions identifying pervasive modern errors. Syndicated across 19th-century Europe and beyond, it framed the Church’s vigorous opposition to liberalism, secularization, and modernist thought.

Today, in light of Vatican II’s reorientation toward religious liberty, the Syllabus holds both historical weight and interpretative complexity.

Historical and Political Backdrop

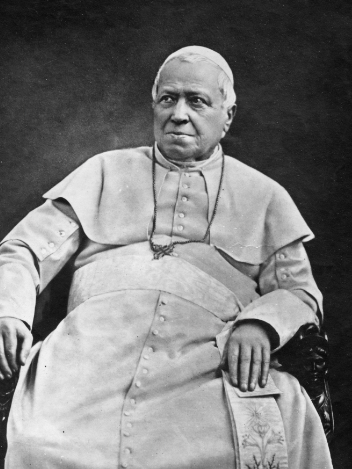

The mid-19th century was a pivotal era for both Europe and the Catholic Church. At the start of his reign in 1846, Pope Pius IX (Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti) displayed surprising liberal leanings—granting amnesty to political exiles and initiating modest reforms. But following the 1848 Revolutions and his brief exile, his tone shifted decisively conservative. Upon his return in 1850, his ministry turned toward restoring papal authority and suppressing nationalist movements.

Meanwhile, the Italian unification (Risorgimento) threatened the sovereignty of the Papal States. In 1864, the September Convention between France and the nascent Kingdom of Italy pressured the French garrison to withdraw from Rome—threatening papal temporal power. It was in this tense climate that Pius IX issued Quanta cura to condemn modern ideologies encroaching on both Church and state.

The Syllabus of Errors—prepared under Cardinal Fornari initially and later finalized with Bishop Gerbet’s pastoral theses—was conceived to summarize the Church’s objections to these ideologies. Though commissioned earlier, its urgent publication in 1864 reflected an ecclesial response to what the Pope saw as a catastrophic continuum of threats.

Under the vibrant energy of his pontificate, Pius IX championed Marian devotion—culminating in the dogma of the Immaculate Conception in 1854—and oversaw remarkable expansion of Church institutions, seminaries, congregations, and hierarchy.Yet his growing conservatism, particularly regarding Church-state relations and doctrinal authority, culminated in the issuance of the Syllabus and ultimately shaped Vatican I’s definition of papal infallibility.

Unpacking Quanta cura and the Syllabus of Errors

On December 8, 1864, Pope Pius IX promulgated the encyclical Quanta cura (“With how great care”), decrying errors such as religious indifferentism, unchecked freedom of conscience, and secularism. Its aim: to protect both Church doctrine and ecclesiastical rights amid the ideological turmoil sweeping Europe.\

Attached to it, the Syllabus of Errors compiled eighty propositions—brief statements summarizing condemned errors—citing previous papal documents rather than providing fresh exposition. It was conceived as a reference tool for bishops who may not have kept pace with the Pope’s extensive allocutions and letters.

These propositions were systematically arranged into ten categories, covering:

- Pantheism, absolute rationalism

- Moderate rationalism

- Indifferentism and latitudinarianism

- Socialism, communism, secret societies, liberal clerical groups

- The Church and its temporal rights

- Relations between Church and civil society

- Ethics and moral relativism

- Principles of marriage and family

- Relative truths in private judgment

- Liberalism and the separation of Church and state

Importantly, the Syllabus didn’t claim to introduce new teachings—it simply consolidated earlier condemnations into a structured index.This approach gave it immediacy and clarity, but also opened the door for misinterpretation, as context was sometimes overlooked.

Reaction and Theological Interpretations

External Response

From secular quarters came fierce criticism: British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone decried the Syllabus as incompatible with civil allegiance, arguing it demanded loyalty to the Pope over the State. To many in Europe, it signaled the Church’s refusal to adapt to modernity.

Critics characterized the Syllabus as absolutist, censorious, and authoritarian—rejecting religious freedom, democratic norms, and the press. Anti-clerical voices used it to argue that the Church was fundamentally opposed to representative government and free expression.

Catholic Defenders and Faithful

Within Catholic circles, more nuanced readings emphasized that the Syllabus was not an infallible declaration and required interpretation within the full context of referenced documents. John Henry Newman, among others, urged readers to consult the underlying papal texts to understand the specific issues addressed.

The Catholic Encyclopedia emphasized that the Syllabus was widely accepted by bishops and councils globally upon its release, understood as a clarifying index rather than new dogma.

Moreover, particularly in places like the United States, many Catholics viewed the Syllabus’s defense of Church autonomy favorably, drawing parallels between its vision of religious liberty and American notions of separation of Church and State.

Contextual and Scholarly Reappraisals

Historians underscore that the Syllabus reflected a defensive posture against active secular encroachments—not a blanket condemnation of science or reason. For instance, Catholic religious orders were deeply engaged in scientific inquiry and missionary-led advancement of knowledge—even during the period the Syllabus was issued.

Theologian Hassard went so far as to call the Syllabus “a mighty articulation of Counter-Revolution,” reinforcing the Pope’s resolve in the face of what he perceived as revolutionary threats to Christianity.

Vatican I & The Doctrinal Context

Following the Syllabus, Pope Pius IX convened the First Vatican Council (1869–1870) to address the theological currents of his era. Among its landmark decisions was the doctrine of papal infallibility, affirming the Pope’s authority, under specific conditions, to define doctrine without error.

The Council’s doctrinal constitution Dei Filius condemned rationalism, socialism, liberalism, materialism, and modernism—resonating with the earlier tone of the Syllabus, but framed in more explicit theological language.

This consolidation reinforced the Papacy’s central role and doctrinal clarity. Yet, even as Vatican I fortified the Papal office, it also inadvertently paved the way for future developments, including the pastoral renewal of Vatican II.

The Modern Catholic Church’s Perspective: Vatican II and Beyond

Shifting Toward Religious Liberty

By the mid-20th century, Catholic thought was evolving. The principle that “error has no rights”—asserting that non-Catholic views held no civil legitimacy—gave way to a more nuanced understanding. The distinction made between moral truth and legal protection became central.

Influential theologians like John Courtney Murray played a critical role in reframing religious freedom, arguing that all individuals possess rights regardless of doctrinal disagreement. Murray’s contributions were acknowledged and embraced by Vatican II, particularly in the Declaration Dignitatis Humanae (1965), affirming religious liberty as a fundamental human right.

Dignitatis Humanae as a Landmark

With Dignitatis Humanae, the Church affirmed that religious freedom is rooted in human dignity and not in the state’s favor toward truth. It recognized the rights of individuals (even in error), distinguished between moral and juridical dimensions of religion, and underscored religious pluralism as socially and morally meaningful.

This represented a profound development from the Syllabus era—a shift from polemical rejection to dialogical affirmation of civil rights and religious engagement.

Present-Day Interpretation

Today, the Syllabus is largely seen as a historical document—an artifact of its time, rather than a normative guide. Church authority has neither formally retracted it nor invoked it in modern teaching. Instead, its relevance lies in understanding the Church’s evolution from protective resistance to proactive engagement with the modern world.

As defenders have long noted—including contemporary Catholic apologists and historians—the Syllabus must be interpreted within its historical, theological, and textual context to avoid misrepresentation.

Modern Lessons & Theological Implications

The Syllabus of Errors serves as a testament to the Church’s struggle to safeguard its autonomy and doctrinal integrity amid 19th-century upheaval. Viewed against the backdrop of revolutions, suppressions, and ideological warfare, it becomes a complex—but vital—chapter in ecclesiastical history.

Modern readers can appreciate how the Syllabus:

- Distills an era’s anxieties—revealing how Church leaders viewed liberalism and secularism.

- Highlights the tension between theology and politics—the balancing act between preserving spiritual authority and adapting to temporal change.

- Illuminates an institutional posture—from normative defense and exclusivity toward dialogical pluralism and religious freedom.

By comparing the Syllabus with Vatican II teaching, one witnesses a pastoral and doctrinal transformation: from confronting “errors” from a posture of authority, to engaging pluralism from the perspective of human dignity and freedom.

Conclusion

Pope Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors is a deeply evocative – and often misunderstood – milestone in Catholic history. Conceived as a firm bulwark against modernization’s threats, it summarised authoritative objections to key ideological trends that seemed to undermine the Church’s spiritual and temporal structures.

Today, articulated through Vatican II’s teachings on religious liberty, human dignity, and pluralism, the Church’s tone has shifted. The Syllabus stands not as a living manifesto, but as a historical signpost—one whose meaning must be parsed with nuance, scholarly rigor, and appreciation for its context.

In an age marked by polarized discourse on faith and modernity, revisiting the Syllabus reminds readers both of the Church’s evolving engagement with the world and the importance of interpreting its legacy through the lens of continued pastoral progress.